George Osborne’s 2016 budget was one that was billed beforehand as one with few nasty surprises so as not to scare the horses on the Chancellor’s own side, who have been awkwardly navigating an uneasy peace ever since the Prime Minister announced the date for the EU referendum in February. That it included in it a measure to cut Personal Independence Payments, a measure that outraged even some Conservative MPs, sparked an internal civil war within the party and gave the Tories perhaps their worst few days since before the 2010 election. This presented Labour with a golden opportunity to exploit government weakness, one that grew bigger with the departure of Iain Duncan Smith, the secretary of state for Work and Pensions, who – ostensibly, at least – resigned over the issue. That they were not able to do this is a fact that will distress even some of Jeremy Corbyn’s loyal supporters.

Many Labour MPs were aghast to see that in Cobyn’s probing of Cameron, who had had to come to the House of Commons on the last Monday before Easter to give a statement following the European Council meeting, the Labour leader neglected to mention Iain Duncan Smith’s evisceration of the government’s welfare policy which, over the previous few days had sent the government into turmoil. Had he forgotten to mention it? Grim-faced Labour MPs could only look on and wonder. It was up to Cameron himself to bring up IDS, when he later paid tribute to his contribution to the government. Instead, Corbyn used his address to ask where George Osborne was, and somewhat inarticulately laid into the absent Chancellor of the Exchequer for the black hole in his budget. Corbyn had been calling for the resignation of the Chancellor even since Duncan Smith had resigned, something that has always seemed unlikely to happen until at least the completion of the next Tory leadership race.

Ultimately, the government performed a U-turn, with the new Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, Stephen Crabb, announcing minutes later in the Commons that the plans to cut Personal Independence would in effect be scrapped. In response to this announcement, the Shadow Secretary of State for Work and Pensions Owen Smith showed Corbyn how it ought to have been done, and made a much better fist of attacking the government. Incidentally, he will have done his own leadership ambitions no harm at all in the process.

Corbyn, to give some credit, obviously recognised the error he had made on Monday, as two days later, during Prime Ministers’ Questions, he finally mentioned IDS. Unfortunately, by this time, the government’s budget had already been voted through, which meant that his line of questioning felt more like an attempt to lock the stable door after the horse had long since bolted. In addition, a new problem had arisen for the Labour leader to distract the Tories from their problems over Europe and unpopularity over welfare reform.

It concerned a list, found by a journalist for The Times but apparently put together by Corbyn allies, that categorised the majority of Labour MPs on their loyalty, neutrality, or hostility towards the leader. The list did contain some strange inaccuracies: more than one journalist said after its publication that they’ve spoken to people in the ‘Core group plus’ category (MPs who aren’t in the inner-circle but are thought of as being on-side) who have moaned to them about the way things have been going. Other MPs joked that they planned to appeal the fact that they had not been placed in the ‘hostile’ category.

Whatever the inaccuracies, though, his was an absolute gift for Cameron, who batted away the Leader of the Opposition’s questions with what many Labour MPs will have regarded as a depressing degree of ease. How had this been allowed to happen? The MP for Cumbria, the noted Corbyn-sceptic John Woodcock wrote a -hastily deleted – tweet soon after Corbyn’s exchanges with the Prime Minister that read: “F***ing disaster. Worse week for Cameron since he came in and that stupid f***ing list makes us into a laughing stock.” One can only imagine he deleted it because he meant to type ‘worst’, not ‘worse’.

This has renewed somewhat the talk of an attempt to oust Corbyn at some point this year, though if it happens, it will not be until after the EU referendum has taken place. But if Sadiq Khan fails to win in London and the party goes backwards everywhere else, it is hard to see how they won’t have a try. They may expect to fail given the strength of feeling that there still is for the current leader within the membership. But they may well decide that it’s worth doing anyway, because come the next party conference in the autumn, the Corbynite wing of the party will attempt to change the rules to make it easier for Corbyn, or someone else like him, to get onto the ballot of any future leadership contest come what may.

Now, admittedly, there has been some more favourable polling in the last week or two, with one putting Labour on level-pegging with the Conservatives, another putting them one point ahead. This seems to be more of a result of the Tories sinking than Labour rising and overtaking the government, but even if that were not the case, it will never be enough: after George Osborne’s omni-shambles budget in 2012, Ed Miliband’s Labour enjoyed double-digit leads over the Tories in the polls and still managed to lose in 2015.

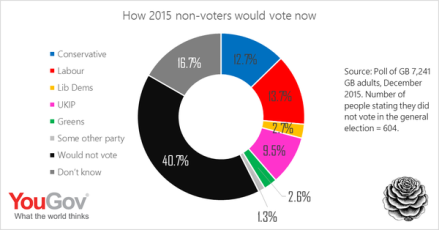

It may be that this recent development is the start of a trend that takes Labour beyond the Tories in the polls, but it cannot be over-emphasised that for Labour to win in 2020, a swing greater than the one it had in its 1997 landslide is required to even get a majority of one. The response to this from some is often that Labour can still win if it attracts people who don’t vote. Research shows that non-voters tend to hold roughly similar views to those who do vote, but even allowing for that, this aim may prove difficult to achieve if polling carried out recently by YouGov and Election Data is to be believed.

This polling shows that only 13.7% of those who didn’t vote last time would vote for Labour now, as opposed to 40.7% of people who still would not vote for anyone. Given that this 13.7% were not moved to visit their local polling station for any party last time, it’s no guarantee that even they would turn out for Labour next time, or that 12.7% wouldn’t turn out for the Tories. This is without even considering the more centrist voters now put off the idea of voting for a Labour government for as long as the current leadership is in charge. In any case, though, it appears that if Labour are trying to attract these people, they are not succeeding.